From a distance, a mountain range looks small. Up close, the peaks are majestic, breathtaking. Are the mountains small? Or are they large? It’s a matter of perspective.

We are in peculiar times. A microscopic mutated microbe has pulled the rug out from under “normal life.” It’s scary- but it’s also a good time to step back and examine what’s “normal” and what’s inconvenient from a different perspective.

Human history has been unfolding for a while now- two hundred years is a blink. However, our lives have little in common with those our forebears lived- even a short two centuries ago.

Consider the way we acquire food. Going to the grocery store is a “normal” experience we take for granted. We walk through automatic doors to see an extensive array of cleanly packaged, artfully displayed, properly inspected food- every type we can imagine- from every corner of the world. Much of it is pre-prepared for our convenience. We choose the delicacies we like best (checking the expiration date), toss them in our large rolling cart, swipe our plasticard, and load them (or watch them loaded) in our 120-horse power (or better) driving machines. We speed over the miles to our climate-controlled home in minutes. We stuff much of the food into the refrigerator (a miracle of convenience itself). We didn’t have to milk the cow or hitch up the mule- or plow, plant, hoe, protect, harvest, or preserve every bite our family eats. Some grocery stores even have employees who shop for us- and deliver! How convenient!

Basking in Convenience does not usually produce the most meaningful life.

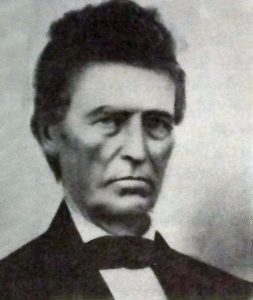

In 1820, my fourth great-grandfather, William Elbert Milburn, the grandson of a Revolutionary War patriot, was twenty-three years old. He lived in Greene County, Tennessee. He farmed to support his wife and baby daughter, but he was called to a life of inconvenience. He was a Methodist minister on the Tennessee frontier.

William preached at camp meetings, but he also rode horseback through the wilderness in all weathers, to settlements and cabins in the Appalachian backwoods. He preached the good news of life and hope in Jesus- and the beauty and blessings of the righteous life- marrying, baptizing, bringing comfort to the sick and grieving- and burying the dead.

Certainly he was often cold- “preaching in log houses with no fireplaces, in dead of winter- when men dressed in skins and holding flintlock rifles over their knees could hardly sit still from the cold.“1 Certainly he was often hungry and lonely- riding for days through forests without seeing another soul, sleeping on the ground. Certainly he was sometimes frightened- by a panther scream in the night, by a thunderstorm high on the mountain, or outnumbered by lawless men who held “the preacher” in contempt. Certainly his heart was grieved- by wrenching poverty, by the countless untimely deaths he was called on to attend, by ignorance and superstition, by the destruction and pain of spiritual darkness.

Why did William choose a life of inconvenience?

William had hope– not a vague “I wish” or “maybe someday” hope-but hope as described by Rabbi/Apostle Paul: confident assurance. He knew the Soul-Saver, Life-Giver, Light-Bringer. William had to take hope where there was none. From his perspective, convenience was a small thing.

And what about those men gathered in the log shelter, a raw wind whipping through the cracks, shivering in their deerskin clothes? How far had they walked through snow and ice to hear the Word of God explained, to sing and pray together? Rifles across their knees, what dangers had they faced along the way? What would they encounter on the way back to their isolated cabins? Were they memorizing the text, the hymns, and the preacher’s words to share with their families?

What is inconvenience compared to truth?

By 1861, William had been in ministry for over forty years. How many miles had he ridden? How many lessons had he taught? How much of his own living had he given away? With his brother Joseph, also a Methodist minister, he had supported his mother and five of his younger siblings after their father’s death. His family had given the land and he helped to build a church, a school, and a cemetery in the village of Milburnton. He had buried his first wife and three of his ten children. He had seen hundreds come to faith at the camp meetings he preached. Now in his mid-sixties, surely he deserved a break- a little convenience.

But William wasn’t beholden to convenience.

Tennessee was the last state to secede from the Union. William, from Quaker stock, expressed his sentiments on the politics of the day: “I was never connected to slavery; was taught from boyhood to believe it was wrong; there was never one hour in which I approved it; I do not expect there ever will be.” 2

His position was not popular. He was harangued, threatened, persecuted. The Bishop questioned his loyalty to the state of Tennessee. Along with three other ministers in the Holston Conference, in 1863, William was expelled from the church.

How inconvenient to stand on principle against popular opinion and the powers-that-be!

At age 67, William joined the 8th Tennessee Calvary volunteers, U.S.A. – as a chaplain. Once more, William mounted his horse to bring hope and light into fear, horror, destruction, and death- and to carry the news of how to find peace with God when there was no peace among people.

At war’s end, the Conference reinstated him, and William continued to minister until his death.

I have a copy of a letter William wrote to his daughter, Evaline Melissa Milburn Fraker, who had moved from Greene County, Tennessee to Whitfield County, Georgia. We listen to family stories, and read histories written by others, but in letters, even though the phrases and spellings are from another time, we can “hear” the thoughts and personalities of the writers.

Milburnton May 14th 1867 Mrs. Evaline Fraker

Dear Daughter, I have writen to Mr. I.N. Hair, Mr. G.P. Fraker, and James Crouch and no answer, and why I know not. It may be they are all dead, and if so, I will excuse them. As I suppose they have no time, no ink or paper, I therefore send you a few lines- it may be you have not forgotten the care of a poor old Father. I hope you have not- my health is not very good, Sarah Ann’s only moderate, the little boys are well. Bro. Ebby was well last Thirsday, at school and no disgrace to a Father, he reads_ taken fine Greek_ tolerable allmost through the corse of mathamaticks. He intends to be a throrrough schollar, if he should live long enough. All our kindred are well so far as I know. I got a letter from Tehue R. Payne last week he, and Jonathan Milburn were all well. Wheat has a fine appearance, I am making no crop this year. I tryed to collect a little money to buy me a horse but failed, and therefore, no crop- I would love much to see you and children. I know you must feel very lonely. I allso want to the widows Hair and Crouch and their Dear Little Children give our love them- we will come to see you all as soon as time money will permit. Sarah Ann says you must come and see us–come soon I may be here I may not be here–I have only three days and four months time of probation untill my three score and ten is out. I am looking every day for my Removal to another mode of being. May God help me to be ready- I want you all to do what is right. Answer this if you are not dead, and if you are, get some of your friends to write soon— You have the best wishes of my heart, learn your children to be pious—I am ever yours in love,

William Milburn SB If you have no paper nor ink invellopes nor stamps let me know and I will send you some.

Nobody can say he didn’t have a sense of humor.

What do I take from the “inconvenient life” of Reverend Milburn?

Perspective- From a distance, many “inconveniences” we are complaining about are ridiculous.

Priorities- Is a self-absorbed, consumerist, entertainment-oriented culture normal? Or is it empty and foolish? What is the best use of my “three score and ten?”

Gratitude- When anxiety takes my breath, the best response is found in the words of an old hymn- “Count Your Blessings.” If I’m thanking God for blessings, I cannot focus on fears.

Great-Grandpa Milburn still speaks over a century and a half– over times that have changed more in a shorter span than any other period in history. One phrase that stands out is his parting advice to his daughter: “Learn your children to be pious.” He did not say”get them the best education,” although he valued education- not “give them the best of everything,” although he gave much in his lifetime- not “get them on the traveling team,” or “be sure they are well-entertained.”

“Learn your children to be pious.”

What does it mean?

“Teach your children to fear the Lord God- to love Him, the full counsel of His Word, and all His children. Embrace a life of inconvenience, if that’s what it takes to bring others hope. Stand for the truth, even if no one stands with you, because in the end, God’s opinion is the only one that matters. We must come to Him on His terms, not our own.” (BTW, A teacher must understand the material before they are qualified to teach it).

Perhaps good will come from the COVID-19 upheaval. Perhaps our “normal” needed adjustment, after all.

Stay well, friends.

PLEASE! Leave a comment- Tell about someone who inspires YOU!

Footnotes: 1 Roster and Soldiers of the Tennessee Society of the Daughters of the American Revolution 1960-1970 Vol. 2, p.566. 2 findagrave.com/memorial/73318767